Despite Hollywood’s veneer of glamor and liberal culture, labor exploitation and gender bias run rampant in the film and television industry. Day-to-day production entertainment workers, often referred to as “below-the-line” crew members, suffer abusive work hours, lack of meal breaks, poverty wages and spontaneous schedule changes in order to keep the multibillion dollar industry running.

Over the last few decades, these abusive practices have gotten worse with major Hollywood studios suppressing workers’ wages and egregiously extending workdays in a drive to increase profit. As a result, workers experience a concerning rise in depression, addiction and even fatal car accidents on their way home. They’re unable to see their children grow up, miss important family events or have to postpone necessary doctor’s appointments out of fear that they may lose their job.

Among the most exploited workers are women. In 2018, a study commissioned by Local 871 of the International Alliance of Theatrical Stage Employees (IATSE) found a significant gender division of labor and pay disparity that remains embedded in the industry. Local 871 crafts like script supervisors are over 90 percent female, art department coordinators are nearly 80 percent female and production coordinators are two-thirds female. These are crucial positions to any media production, and yet these workers are paid hundreds if not thousands of dollars per week less than their counterparts in comparable male-dominated crafts.

If a script supervisor, in charge of ensuring continuity between shots, misses any details of the script it can cost the studios several thousands of dollars in reshoots. If an art department coordinator doesn’t obtain legal clearance for products or artwork appearing on screen, the studios can be plagued with costly and time-consuming lawsuits. If a production coordinator, who interacts with production companies, insurance and legal departments, agents, managers, vendors, air-conditioning, caterers, and practically every other department, is absent from work, the day-to-day logistics of a project can fall apart very quickly.

The high level of skill and reliance on these positions in the industry means that women are often unable to take a day off while on the job due to the amount of training needed to fill the position. In an IATSE Local 871 roundtable, writer’s assistant Amy Thurlow speaks to this saying, “If we’re gone for a day or we’re gone for an hour or two hours, there’s someone who urgently needs us. I’ve put out [script] pages from weddings, I’ve pulled over to the side of the road [to put out pages], I put out pages this morning. There’s no time off with these jobs. I think there’s a way to have balance if you’re at least making money that can afford you that.”

The industry’s current gender discrimination heralds back to the early days of cinema. During the silent era (1912-1929), the industry of filmmaking was still extremely new and experimental in both processes and equipment. Film, at this time, was largely seen as a novelty, a passing fad of working-class entertainment by Wall Street investors and therefore unprofitable and unimportant. This made it easier for women to gain opportunities behind the camera. Small independent film studios, many of them run by women, thrived during this period. Studios were able to focus on film as an art form, prioritizing innovation, experimentation, and encouraging small production teams to learn the entire process of filmmaking regardless of gender.

As a result, women wrote roughly half of all films and were involved in nearly every aspect of production including editing, casting, set design and costume design. All the highest-paid screenwriters were women and many of the top directors were women. Women largely pioneered the development of filmmaking into an industry and an artistic medium.

However, as soon as movies became more widely recognized as commercially successful, Wall Street capitalists began to invest and consolidate these studios into fewer and more powerful business structures. These capitalists—concerned with protecting their own interests—were less likely to financially back women filmmakers. Women not only were seen as too incompetent to run a business but many of the films made by women explored radical and feminist themes around abortion, birth control and gender identity that directly threatened the capitalist class. The economic crash of the Great Depression also dealt a deadly financial blow against independent film studios, where women were most prominent.

With Wall Street investors at the helm, moviemaking was reorganized into an assembly line and the gender division of labor in film production became much more institutionalized. The arrival of the corporate studio system (1920-1950s) meant that women were rarely given the chance to direct and were instead relegated to lower status secretarial support jobs like “script girl” or “continuity girl”, because this work was often thought of as “women’s work.”

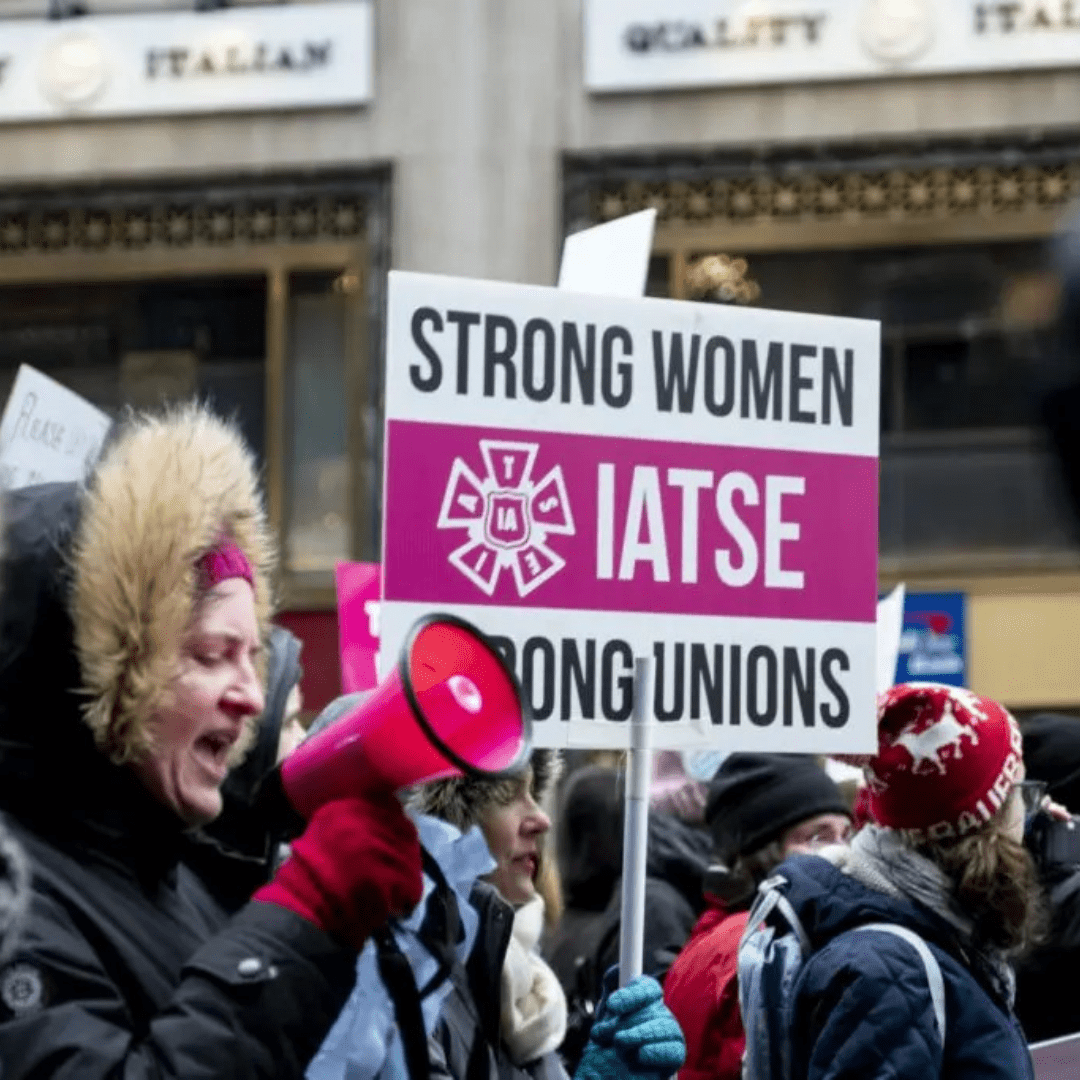

To this day, women continue to struggle against this gendered industry culture that devalues their contributions. IATSE Local 871 has been a leading force in this fight, launching the #ReelEquity campaign in 2018 and a call to end gender pay bias industry-wide. That same year, Local 871 also successfully unionized script coordinators and writers assistants, both of which are historically poorly-paid support-staff roles. Consciousness has grown quickly across the industry, contributing greatly to 2019’s #PayUpHollywood movement in which assistants shared their stories of low wages and unhealthy working conditions.

In 2021, the organizing efforts of women workers in Local 871 catapulted the demand for a living wage to the forefront of contract negotiations. With solidarity among IATSE’s 13 Hollywood locals at an all-time high, they worked to prioritize raising the minimum wage for the lowest paid female-dominated crafts. Bolstered by both the #PayUpHollywood and #MeToo movements, Local 871 members launched the #IALivingWage campaign in order to tell their stories of financial struggle and garner public support for the growing labor unrest.

On October 4 2021, the sleeping giant of Hollywood labor exploded. In defiance of the studios, 60,000 entertainment workers of IATSE voted overwhelmingly to authorize a historic nationwide strike. Results show that 90 percent of eligible union voters cast ballots, with more than 98 percent of votes cast in support of the strike, giving IATSE leadership major leverage in its fight for a fair contract.

Susanna Boney, Local 871 member, art department coordinator, and mother shared her story and her reasons for voting yes to strike: “It is unfathomable to anyone in my life who does not work in the industry that yes, I am working 12 hours a day, not including the commute. I sometimes do not see my baby awake at all. I cry a lot on my morning commutes, I miss my son. Not only can we not afford daycare with my paycheck, but with COVID and a recent hospital stay, we just don’t have options for my husband NOT to be the full-time caregiver.”

In the eleventh hour, IATSE tentatively agreed to a contract with the studios, averting a nationwide strike. However, only a few days later, cinematographer Halyna Hutchins was killed on the set of the film “Rust” in New Mexico as a result of this same cost-cutting on labor and producer greed. In the midst of a ratification vote, many IATSE members saw the tragedy as further highlighting these systematic issues and bolstering many towards rejecting the new tentative contract. The IATSE contract struggle won significant material gains for its workers. With the latest contract, IATSE was able to win a 62 percent wage increase for the lowest paid workers, most of whom are women. This is a huge win for the most oppressed and will undoubtedly change lives. The agreement ratification also passed by a razor-slim margin of the membership, revealing the deep discontent among workers over the status quo and signaling potential for a growing labor struggle ahead.

It is clear that this Hollywood labor rebellion would not have been possible without the many years of struggle by women workers in their union. While there is still much work to do, the participation and leadership of women in their unions is absolutely necessary for a strong labor movement. Hollywood has always been built off the backs of thousands of below the line workers who risk life and limp only to make multibillion dollar corporations insane profits. If the studio executives were absent, the movies, television shows, and animations would still get made. It is the workers who run the film and television industry, and it is they who will change it.