A single mother, communist labor organizer and balladeer, Ella May Wiggins was born into a logging family in the Appalachian mountains of Tennessee in 1900. She learned the tragedy of the poor working conditions early on, as her father, mother, and four of her 12 siblings died from illness or work related accidents. While still in her teens, she wed a logger named John Wiggins. Having very little family to ground them in Tennessee, Ella and John began searching for work outside of the mountains at textile mills. They chased the promise of financial stability proffered by the textile mills, only to find the same thing every time: inhumane hours and insufficient pay.

As they hopped from mill to mill, the family grew. Ella May Wiggins raised nine children in total. Four of her children fell ill with whooping cough, and the family could not afford to buy them medicine even while working 12-hour shifts. Tragically, Ella May watched all four pass away from the disease. The experience stuck with her for the rest of her life. At rallies, Ella May would share this tragic story to spur other mothers to join her in striking for better working conditions, saying:

“I’m the mother of nine. Four of them died with the whooping cough, all at once. . . . I asked the super to put me on the day-shift so I could tend ’em, but he wouldn’t… So I had to quit my job and then there wasn’t any money for medicine, so they just died. I never could do anything for my children, not even keep ’em alive, it seems. That’s why I’m for the union, so I can do better for them.”

After this tragic loss, the Wiggins family settled down in Stumptown, a predominantly African American community, in Gaston County, North Carolina. Not long after that, John Wiggins left the family, never to return. At this time, Ella May reverted to her maiden name, and dropped “Wiggins” entirely. Now in her twenties, she was earning $9 for working a 72-hour work week at American Mill No. 2, trying to make ends meet and care for her remaining five children. It was here that she learned of the Loray Mill Strike that was happening only seven miles away from her. The Loray strike was being led by the Communist-led National Textile Workers’ Union. Ella May walked out and joined the NTWU. At the Loray Mill, strikers’ demands included a minimum weekly wage of $20, equal pay for women and a 40-hour work week. For women like Ella May, the union’s demands resonated. She became heavily involved with the NTWU and became an outspoken labor leader at a time when labor organizing was downright dangerous.

Ella May’s contributions to the union were twofold: First, she raised the spirits of striking workers by writing and singing songs. Her most famous ballad is the “Mill Mother’s Lament”, which outlined her own reasons for joining a union. She sang:

Our wages are too low

It is for our little children

That seem to us so dear

But for us nor them dear workers

The bosses do not care

But understand all workers

Our union they do fear

Let’s stand together

And have a union here

These words struck a chord with women workers who were witnessing the effects of poverty and exploitation on their children and themselves first-hand. Some, like Ella May, were the sole breadwinners of their homes. For the women workers listening, the strike’s demand for equal pay for women was a life and death issue.

Second, Ella May’s experience working side-by-side with Black workers and living in a predominantly Black community sharpened her commitment to solidarity with African American workers. She independently organized a group of Black workers, friends and neighbors in Stumptown to join the union, and her local NTWU voted to admit African American workers to the union in a close vote. When Black laborers were invited to attend a union meeting but then told to sit in a segregated section, Ella May sat in the section with them in a show of solidarity. She knew that their futures were inextricably entwined, and that the only path forward to prosperity was solidarity.

As the strike continued on, some conservative union leaders attempted to downplay the more radical and progressive stances of the NTWU, including the racial solidarity Ella May and her fellow workers had fought so hard to forge. In a clash between union members and police, the chief of police in Gastonia County was killed and the strike began to collapse. As hostility against the union intensified, Ella May stood firm and refused to return to work. She continued to sing and speak, and was on her way to speak at a rally on September 14 when armed vigilantes murdered her. She was only 29 years old.

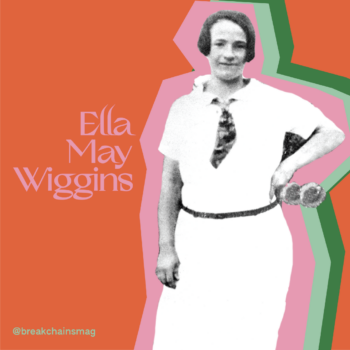

Though her life was cut short too early, Ella May Wiggins’ sense of struggle and contribution to the workers’ movement burned brightly. Perhaps one of the most widely circulated photos of Ella May Wiggins is the photo used for her obituary. She is smiling slightly in a white collared dress and a tie, with one hand on her hip. In that hand, she is holding a sunflower. She is a vision of confidence and determination, and her eyes look seasoned with struggle and loss. The words for her obituary could not have been more appropriate:

“She died carrying the torch of social justice”

Ella May was remembered from then on as a martyr in the fight for labor rights. She lived fiercely and boldly, and was blessed with an instinct for equality that preceded the Civil Rights Movement by 30 years. Her songs and speeches speak to how women’s issues are labor issues, and she continues to inspire those who dream of a better world for the children they hold dear. Comrade Ella May, ¡presente!